|

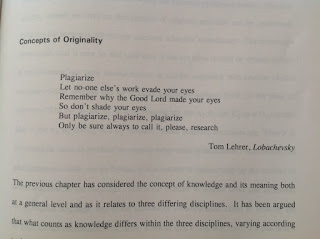

| Properly cited lyrics, so it isn't plagiarism |

The problem is simple to describe. There is a concern that some students are buying essays written by others and passing them off as their own. This is plagiarism, and is cheating. It isn’t clear how many students are doing this, but a few businesses which supply such essays are obviously doing decent business, and by implication the number of students doing this is non-negligible. The Telegraph cites 20,000.

The QAA recommend a three-pronged approach:

- Partnership working by the sector to tackle the problem

- The possibility of legislation, perhaps like that in New Zealand

- Using regulators to prevent essay mills from advertising.

Jo Johnson’s statement focuses on the first and third approaches: the sector should sort it out, by means of guidelines and tougher penalties for students; the QAA should also go after the essay mills’ advertising. Legislation isn’t ruled out as a possibility, but is definitely kicked into the long grass. And, gratifyingly for the minister, some proper outraged press coverage about those naughty students.

I’m torn as to the best approach on this.

Early in my career I handled cases of student cheating, and plagiarism was by far the most common ‘irregularity’. This was in the very early days of the internet; pre Turnitin, and spotting plagiarism was down to eagle-eyed markers. And it was often pretty obvious: passages copied from books without editing, meaning that ‘as I argued on page 34’ for instance, showed up as out of place in a 6 page essay. Often the source material was cited in the bibliography. Whilst there was no doubt that the work had been copied, and without proper attribution, it was difficult with examples like this to see it as a deliberate attempt to deceive, as opposed to a complete lack of understanding about what the essay was trying to test. Often coupled with poor self-organisation meaning that at the last minute the student panicked.

In such cases throwing the book at the student would have been wrong, and that was often the academic judgement. A clear fail for the essay; a requirement to resubmit; and work to help the student understands what the problem was: this was a good remedy.

In the case of a student submitting as their own an essay which they’ve bought online, it is harder to be so forgiving. There seems to be more agency involved in committing the exam irregularity. Buying an essay and passing it off really isn’t a failure to understand the practices of academic referencing; it’s a straightforward attempt to cheat. And on that argument, the minister is right. Sort it out, HE sector.

But legislation surely can’t be a bad thing to get on with. Even if the ‘crime’ is committed by the student who submits the purchased essay, there really isn’t an argument for leaving the essay providers untouched. The notion that these are bought for ‘research’ purposes is laughable. The idea that tailored exemplars are a good way to learn is not a strong one. (The use of model answers afterwards to help feed back to students on their performance is a different question.) And the New Zealand law, which empowers the higher education quality regulator to prosecute essay mills, does not look like a bad law.

Would it solve the problem entirely? No – essay mills may be based outside the UK, and beyond the scope of the law. Would it help to convey the message that the practice is wrong? Yes. Would it help to demonstrate that the UK takes academic standards seriously? Yes. Is there a convenient current parliamentary vehicle to achieve this? Unbelievably, yes there is. The minister could do more to make this happen now.

There’s another angle here. A student who submits a plagiarised essay may get caught, and face a penalty, or may not. But what is absolutely certain is that they will not learn as much about the essay topic as a student who reads and writes and submits honestly, even if they fail or get a poor mark. The plagiariser knows less than the honest student. And this cost is borne throughout their life. To plagiarise is to fail.

If universities could convey this message better to students, we might be getting somewhere important.